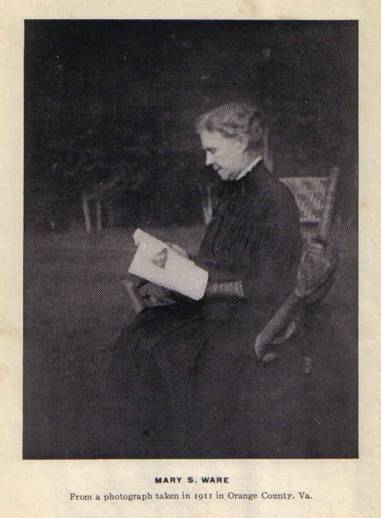

A New World through Old Eyes with Reminiscences from My Life (Putnam, New York, 1923) was written by Mary Smith Dabney Ware (1842-1931). It was the second of three books she wrote on her long travels around the world. The books consist mainly of letters written to family at home. The first was titled The Old World through Old Eyes (Putnam, New York, 1917). The last was called From Mexico to Russia (Ferris Printing Co., New York, 1929).

Below are Mary Ware’s Reminiscences from the second book. The first 224 pages of the book—not reproduced here—tell of 14 years of travels through Europe and the Middle East following World War I, describing the “new world” arising out of the devastation of the war. The remaining 67 pages are Mary Ware’s Reminiscences of growing up in Raymond, Mississippi, where her father Augustine L. Dabney (1800-1878) was a lawyer and Probate Judge. Her mother was Elizabeth Osborne Smith (1810-1905). The family had emigrated from Virginia in 1835 with relatives and other families. Mary Ware’s experiences during the Civil War (in which three of her brothers fought and survived) include audiences with Union Generals Grant, Sherman, and McPherson after the fall of Vicksburg. She met her future husband, Lt. William Lynch Ware, while caring for wounded soldiers, and they were married during his convalescence following a second, more serious wound in the chest. She ended her days at Sewanee, Tennessee, where her son Sedley Ware was a professor at the University of the South.

Reminiscences of my

Life

[226]

[227]

PREFACE

These somewhat disjointed Reminiscences from my long life were begun in Sofia at the home of those good people, Graham and Aubrey Kemper. They were continued in Constantinople and in other cities of the Near East, then put aside to be resumed and hastily finished on this ship, "The Kroonland," which is bearing me back to America. They were written primarily for my grandchildren that they might not altogether forget their old grandmother. To die and be forgotten is the fate of all humanity. "Yet e'en from the tomb the voice of Nature cries!" and we long to live on for a while in the memory of those we love. To this end have I penned these pages, hoping that truth, however humble, is not wholly without value and that my grandchildren may find, perchance, in these records something of guidance or of encouragement.

[228]

[229]

REMINISCENCES

When I was old enough to become conscious of my surroundings I saw myself one of a large family of brothers and sisters, all of good normal intelligence and of really high character. I was perhaps the most stupid. It is certain that I could never learn arithmetic or spelling. My father for a few months, or perhaps it was only weeks, employed my oldest brother to teach us younger children. He was not what one would call heaven-born or gifted for the task. He would put questions in mental arithmetic to me: "If I pay ten cents for a pound of nails what must I pay for ten pounds?" Of course I was utterly unable to give any satisfactory guess, or any answer whatever. Then he would take me up and set me on a high narrow press called Brook's Press because a carpenter of that name had hammered it together and painted it a dark red. It was very wobbly and I terribly afraid, but it did not help me in mental arithmetic. One afternoon stands out in my memory. It had rained and the sun had burst out. Perhaps it was springtime I had been dismissed from the schoolroom after having been duly punished for my stupidity. I had never before thought of nature, whether it was beautiful

[230]

or not, but suffering had quickened to some extent my intelligence. As I walked in the garden I exclaimed to myself: "How beautiful the world would be without arithmetic." Those glittering rain drops still remain fresh in my memory. In those days there were no Public Schools. When a man died and left a helpless widow and children, the neighbors said: "Let her open a school." If a man had failed in all else they said likewise "Let him open a school." Of course there was no question of grading. We all recited in the village schoolroom.

At the closing hour all the children stood up, big and little, for a spelling competition. I of course was at the foot with another unfortunate called Babe. As sympathetic friends could whisper to us we were at length put in a class to ourselves, examples in the Spartan sense, and there we would stand before all the others, helpless, abject, rolling our eyes round to the four corners of the room, appealing mutely for help where none could be had. One day as I was debating whether to say "e" or "i" I caught my sister Nannie's glance and she put her finger over her eye. I answered wrong as usual, and on coming out of school my sisters called out, "You goose, didn't you see Nannie put her finger to her eye?" "Yes, I did, but I thought she got a gnat in it."

My mother gave us a great deal of religious instruction. We were sent to Sunday School in the morning, and in the afternoon she held long services at home. She read all the fearful denunciations for sin she could find from beginning to end of the Bible, so that when I heard the

[231]

wind rattling the windows at night I thought the Devil had come to take me off, and suffered great mental anguish. We were brought up in terrible fear of Satan, into whose hands God in His wrath seemed to wish to deliver us. Yet my mother taught us that whatever we desired ardently, if it were good for us, we could obtain by earnest prayer. Now we had dreadful storms in Mississippi. During one of these our stable was blown down and the servants came running into the house to tell us the terrible news, for our mule was in the stable. There was great consternation and grief in the entire household, but I determined to save our mule by divine intervention. I ran to my room, shut the door, and throwing myself on my knees prayed with all my heart and soul for our good mule. I told God how good and faithful he was and sobbed out, "Save our good mule, Save our good mule, this once," but the mule died after much suffering. I concluded then that it was useless to pray for animals, certainly not for mules. Now we children were told by someone that everyone had a verse in the thirty-first chapter of Proverbs. My birthday, as set down in the family Bible, was on the 27th, but the 26th verse pleased me greatly. "She openeth her mouth with wisdom, and on her tongue is the law of kindness." My mother, too, had told me that I was born between the 26th and the 27th, so I chose that verse, though I really had no right to it. I concluded then to pray for wisdom and goodness, which I did every night after the, "Now I lay me down to sleep" had been disposed of. I reasoned that as nothing could be better for people than

[232]

wisdom and goodness, God would surely grant the request. But this prayer, too, has remained unanswered, and my life has been full of regrets for things done which more wisdom and goodness would have averted. I suppose it is our duty to make ourselves wise and good and not expect the Lord to intervene, just as we should not wish our children to be eternally begging us for things which they should bestir themselves to accomplish by their own endeavors. My father was a lawyer and as he had been elected more than once Probate Judge, was called Judge Dabney. He had had a college education and loved literature far more than law. He was singularly devoid of shrewdness so necessary to a lawyer's success. He lost therefore what fortune he had inherited and most of my mother's. He had a passion for trying experiments, which was the subject of many a joke from my mother, for none of his experiments succeeded, but she had a profound respect for his literary attainments, and indeed few fathers retained to an equal degree the reverential attachment of their children. There were never any quarrels in our household. We had nothing to inherit after the slaves were set free, and we were always willing to help each other. My mother was a very busy woman, though we had a number of household slaves. There were so many children, nine of us. Then the servants and their children had to be provided for. When the day's work was over she would sit in the twilight with her knitting. Unfortunately for her peace of mind she attached too much importance to the differences between the Christian Churches. She was

[233]

ever conscious that straight and narrow was the way that led to salvation. She was ever fearful that she might have wandered into that broader way with its wide open portals leading to destruction. She longed for security. In Virginia she had been brought up in the Episcopal Church but when she came to Mississippi there was no such church in the little town of Raymond where my father settled, nor was there any prospect of one. She therefore joined the Methodist, but a few years later her Baptist friends persuaded her to come over to them. My father thought this change unnecessary, but in the case of religious exaltation obstacles only strengthen the will to overcome them. I believe that I was the only member of our family who accompanied my mother to the little stream near Raymond where the Baptists practised the primitive rite of immersion and I did so surreptitiously. I crept up on the little seat behind the buggy and made the trip, but I remember nothing else that occurred, as I was very young. Much later an Episcopal Church was established in Raymond and we frequently had the pleasure of entertaining our good old Bishop Green, one of the holiest and most beautiful old men I have ever seen. It is related of this saintly man, I do not know on what authority, that he was once in a town where Patti was singing. A ticket was sent to the Bishop, but because it was during Lent, he did not go to hear her. As Patti was leaving the town, her carriage met that in which sat the Bishop. He stopped and got out to make his excuses to the great singer. She on seeing that beautiful, saintly face and hearing that wonderful, musical

[234]

voice, sprang out of her carriage and begged his benediction, kneeling before him. After my marriage my father moved to Crystal Springs where my oldest brother resided. Here my mother fell under the influence of the Presbyterians. I received one day at my home in Jackson a hasty summons to Crystal Springs. There I found my father and my eldest sister Nannie much agitated. My mother wished to join the Presbyterians, though an Episcopal church was in the town, also a Methodist and a Baptist. They therefore thought it was not only unreasonable but a little mortifying for the family. I took a different view. If it were necessary to my mother's peace of mind, as it surely was, for she had taken to her bed, ill, was it not a small sacrifice for so priceless a boon! I persuaded them to my way of thinking and we sent for the Presbyterian minister, a most worthy man in spite of his peculiar name Rowdybush. Mr. Rowdybush acted with wonderful tact. He offered my mother every privilege of his church without the formality of joining it, so I returned to husband and children leaving peace behind me. Later on some person, whose intentions I considered at least doubtful, sent my mother a periodical depicting the labors and hopes of the Reformed Episcopalians. This periodical, coming regularly to her address, was carefully read and digested till at last these would-be reformers took on the complexion of the early Apostles. She imagined them going from place to place with staff and sandals and in humble raiment intent only on their holy mission. It was the desire to be near this new church which led her to influence my father to take her

[235]

to California with me. I knew nothing of all this, but in Santa Rosa, California, she spoke freely of her intentions to my sister Martha. This sister was a woman of rare intelligence. She went down to San Francisco and had an interview with the Reformed pastor. She wrote an account of it in which, among other things, she mentioned casually "Mr. X made a very favorable impression on me. He is very gentlemanly, quite interesting and very well dressed." We heard no more of the Reformed clergyman, and so at last, after many wanderings, my mother found the peace she had sought so ardently. She had followed her conscience whither it had led her, and was never swayed by worldly considerations.

When I was still a small child my mother sent me, for reasons of health, to the country for some weeks to a friend of hers, Mrs. Summers, a cousin of my uncle's wife. We all called her Cousin Maria Jane, and a very good woman she was. I have never forgotten the first dinner in that plantation home where I was asked what part of the chicken I preferred. Never before had I been treated with such distinction. I answered proudly, "I will take the leg." I thought it was the biggest piece. My visit there was one of pure delight. There were many children, and I was permitted to play and roam over the big garden and nearby wood the whole day with my young companions. In the twilight we beat the shrubbery, that is the older children did so, we others picked up the poor little birds that had taken refuge there, and then hastening to the big nursery we picked and stuffed them with buttered bread crumbs and hung them

[236]

on strings in front of the great open fire-place. They were very small, the poor little birds, but we ate them ravenously though we had all the supper we could possibly swallow. The whole process of capturing, preparing, cooking and devouring them was thrilling. I had never been in such a children's Paradise before, and I must add that the superb health I enjoyed contributed immensely to my happiness. In Raymond during the cold months I suffered greatly from headaches and dyspepsia. There were in those days no ships bringing fruit to our shores, no railways distributing their precious cargoes throughout the land, so we only enjoyed an abundance of fruit in summer from our orchards. When Cousin Maria Jane took me home I was at first extremely unhappy. I had led a life of such freedom on the plantation, almost like a little savage, that the return to restraint and monotony was very painful. I remember distinctly that I was ashamed of the dinner my mother offered Cousin Maria Jane, and particularly ashamed that cabbage formed a part of it. I cannot remember anything about my brothers or sisters at this home coming. Cousin Maria Jane left that afternoon and when supper was over I sat in a low chair by the fire in my mother's room. She and my father were silently occupied at the table where the lamp burned. I listened to the far off barking of the village dogs and thought that my little world was too sad and dreary for words. That picture of utter misery is still clear in my mind associated with the barking of village dogs.

Our little town was very religious. We had frequent

[237]

protracted meetings in our churches. One day, during one of these revivals, a lady called to see my mother while I was undergoing punishment for some forgotten offense by being tied to the bed post. I felt deeply the humiliation and stood as close to the bed as possible to hide the cord while listening to the conversation. The lady related to my mother that the evening before her son had attended the revival services and had wanted very much to obey the call to come to the mourners' bench and get religion, but could not do so because he didn't have a pocket handkerchief. This recital threw me into a state of mental consternation. I felt that here was a boy much older and bigger than I, a really big boy, who couldn't get religion and save his soul from those terrible tortures, which awaited us all in the hereafter, because he did not have a pocket handkerchief. I do not remember ever to have been trusted with a pocket handkerchief when I was a small child. I had however an apron upon which I could always weep freely, but that poor boy couldn't weep on his apron, because he did not have any. If I had not been so stupid I might have thought that he could go to services next day with a handkerchief in each of his pockets, but we all had the feeling that when the "call" came you must respond. The case of this boy remained for a long time a tragedy in my memory. My religious ideals were so narrowly puritanical, it was only gradually and after many years that a higher conception of the relations between the Creator and His earthly children formed itself in my mind.

[238]

Raymond, where I was born and brought up, was a very small town, scarcely more than five hundred whites. My sister Letitia once said of it that its only immigrants were the babies and its only emigrants the dead, but this was hardly correct inasmuch as its young men went away in search of fortune.

I do not remember that my parents ever gave any evening parties except at Christmas time. Then they invited their friends to partake of eggnog and delicious home-made cake, before the introduction of baking powders. There were always two bowls, one for those who liked a goodly portion of liquor, though they were pretty silent about it, and one for those who explained at length that they could not possibly take theirs strong. All this caused much lively banter and merriment. Then the company would adjourn to our little parlor where they played on the piano and sang. My mother would call for different pieces, which caused in me both astonishment and admiration, for I could not possibly distinguish one tune from another. I would say to myself, "How wonderful my mother is! How can she know that the pieces she is calling for have not already been played? She is asking for the 'Battle of Prague,' we have already had a very noisy piece, perhaps that was the 'Battle of Prague.'" After the company were all gone my father and mother would linger for awhile over the parlor fire and discuss the evening. My father would begin: "I believe, old Lady (he always called her old Lady), our parties are the pleasantest given in the town. I think indeed that this is admitted by all our friends. How they

[239]

praised our eggnog and the good plum cake tonight! They feel at home in our house. They laugh and joke without restraint, no one is bored for a moment." Then my mother: "Yes, I have known all that a long time. When we go out to parties, how stiff and formal they are! I am sure that we Virginians are the only people who know how to make good eggnog. Everybody acknowledges that, etc." I would listen to this, my heart swelling with pride within me, and I would say to myself, "In all this great big town there are no such parties like those given by my parents," and I would became inordinately vainglorious.

My father was extremely fond of music and had all his daughters taught by a professor. He hoped that among us all some latent talent would be developed, but my sisters seemed to have little more taste for music than I. I had, however, a characteristic so strongly marked that it appeared in my early childhood and will follow me to my grave. I could never endure to have any task handing over me. I had to get it done, to get it off my mind; then only I felt free. My father told me I must practice an hour every day. This duty was highly distasteful, as I had no ear for music, consequently I bestirred myself immediately after breakfast to get it off my hands. Then I could follow lightheartedly for the rest of the day my own inclinations. At noon when my father returned from his office he always asked each of us if we had practiced. I could always answer "Yes, Sir." I must say in excuse for my elder sisters, for I was the fourth daughter, that their time was worth far more

[240]

than mine. Nannie, the eldest, was fond of sewing. Elizabeth the second was even as a child one of the most useful persons I have ever seen. Gradually my mother put the housekeeping and much of the care of the other children on her, though she was still very young. She was a second mother to us all. She developed such skill in cutting and fitting garments that my aunt would send for her to come to the plantation to show her how to cut and fit her children's clothes. Indeed in every respect, in efficiency, in intelligence and in character she was far above the average. Her time was therefore never wasted and the stupid piano lessons were neglected for more pressing duties. My third sister Martha had really remarkable literary gifts. I have never heard Shakespeare or the Bible read as she could read them; no contortions of the body, or of the face like so-called elocutionists, but with such intimate appreciation of the meaning and with such simplicity of manner that she could make the dullest understand the noblest conceptions of Shakespeare and thrill them with the lofty eloquence of the Prophets. She had studied and found out every remarkable passage in the Works of Shakespeare and I often sat and listened to her reading in silent wonder and admiration. I am convinced she would have made a celebrated actress, but in our family and at that time no such thought ever arose in our minds. We children had never seen a theater or acting till long after we were grown. As for me I possessed neither practical usefulness in the house nor the slighest literary ability. What I learned I learned painfully, with much labor, and only through

[241]

a certain tenacity of purpose. I, therefore, having nothing else on my mind, hastened to get through with my hour at the piano. I learned the pieces the Professor taught me, but I could not learn without his aid. I saw that he sometimes corrected a note, I knew that I was perfectly incapable of doing this, so with confidence undermined, I was afraid of undertaking any new piece of music without help. I was, however, the only one of the daughters who played, and my father took great pleasure in hearing me.

When I was fourteen and a half years old two sisters from Jackson paid a long visit to Raymond. We became inseparable companions during this time and they persuaded me to urge my parents to send me to a boarding school in Jackson, where they were to be day pupils that autumn. I was too young to recognize the impossible in anything that I desired very much. My mother too pleaded for me and my father recalled to mind that there was a Virginia family in Jackson who always sustained him at election time. They lived very near the boarding school, so he rode over to that city one day and made arrangements to board me with them for $8.00 a month. Three of my cousins were entered in this same boarding school. The eldest, Susan Dabney, afterwards Mrs. Lyell Smedes, was a parlor boarder. My eldest brother Fred took me to Jackson and gave me $5.00 of his earnings. I adored this brother. He was so handsome and big and strong, and his heart and soul and mind were all built on a big scale. I put this precious five dollar gold piece away carefully. I found the lady of the house

[242]

where I was to live an invalid. She was in bed all the time I was there and turned over the housekeeping and her children to an unmarried sister of uncertain age. In a short time after I became an inmate of the household this sister manifested great hostility to me. This made me very miserable as I was completely in her power. I asked her if I had offended her in any way and begged forgiveness if I had done so. I never knew the cause of this hostility till some years afterwards. It seems she was very much in love with a young man, her junior by some years. He in his turn was much in love with my cousin Susan Dabney. When this young man learned that I was Susan's cousin he was very polite to me. This politeness was misinterpreted by the sister of my hostess, who quickly began to regard me as a possible rival, and from that moment on she made my stay in the house a torture to me. One day at the school the wife of the principal, Mrs. Ozanne, took me aside and said, "You have been looking so unhappy lately that I wish to know the reason." I broke down in a flood of tears as I told her how cruelly I was treated. She had my things moved over to the school house the same day and was one of the kindest friends I ever had. I had naturally expected that the two sisters who had visited Raymond would have greeted my arrival at the school with cordiality. They were indeed the cause of my being there, but they were cold and constrained in their manner. I was too unsophisticated to understand the cause. The family in which I was living did not move in the same social circle. Their enigmatical and apparently heartless conduct to-

[243]

gether with the unhappy life I was leading in my Jackson home made me a real object of pity. I worked very hard too without making progress for I had not the slightest preparation for the senior class in the school, except that I could read. I did not know even the rudiments of grammar or arithmetic. There were so many to go to school in our house in Raymond that most of the time my mother undertook to teach me herself. I used to follow her around in the mornings as she attended to her various duties begging her to hear my lessons, impelled by that ever-pressing necessity to get unpleasant duties off my mind.

That winter there came to Jackson a phrenologist who created a great sensation among us school girls. We heard from those who had visited him of the wonderful characters and intellectual attributes he had so freely endowed them with and we longed to possess those marvelous credentials to show our families and friends. Each girl who went to the wise man came back enchanted, till a perfect frenzy seized us to put our heads under the hands of the magician. I took out my five dollars, for that was the price, considering that I could not possibly spend it to better advantage, and betook myself to him. I was delighted to hear all the nice things he said about me as he passed his hands over my silly head, dictating to his Secretary. I handed over my gold piece and came away with my treasure. But when I opened it in my room to re-assure myself of all the flattering statements I was led to expect in it, to my horror I found that throughout the document I was given the masculine

[244]

gender, "This young man has a highly developed, etc. This man young man has such and such a bump of so and so." Now the bump of sensitiveness at fifteen is perhaps more highly developed than any other in a girl, and I was so profoundly mortified that I dared not show the document to my friends or family. I regretted too late my five dollars thrown away on those two impostors, who took my money and then treated me so ignominiously. My good friend Mrs. Ozanne asked me to teach her little children an hour a day, but at fifteen I had not the slightest idea of how to teach, and I can truthfully say they learned nothing, yet that was the price paid for my board, that and the hire of a slave girl not quite my age. Long afterwards when I undertook to teach my own children I was singularly successful. I put a tiny piece of candy on each letter that was called correctly. This made the alphabet highly attractive and exciting and I was begged for frequent lessons. The syllables were treated in the same way and reading followed rapidly.

At this boarding-school I practiced six hours every day. I got up at four in the morning and went to the cold music room where my fingers were so stiff I could hardly move them over the keys. Then I practiced two hours more in the afternoon. I wonder now how Mr. and Mrs. Ozanne stood being waked up at four in the morning, for their room adjoined the music room. I should never have been permitted to devote so many hours to the piano, to the neglect of everything else. My health was ruined by it for some time, and it absorbed all my

[245]

strength and energy. It was perfect folly too, as my music teacher told me long afterwards. He said two hours daily would have been better. I should have spent those wasted hours in making good my want of preparation for the senior class. I remained in that school for two years. Then after one year at home my sister Martha and I applied for and received a position in a girls' boarding-school in Claiborne County, Mississippi, she to teach the primary class and I to give lessons on the piano. Of course I was unfitted for such a task. I was not eighteen till the very end of that year 1860, and even had I been much older I had no natural aptitude for music, no ear for it whatever. I believe my sister became a very efficient teacher, but I had no such brilliant record ahead of me. It seems incredible to me now when I look back on that episode in my life. The one thing which consoled me and still consoles me is that I never received a penny for the winter I taught in that school. It is true I had board and lodging which I hardly think my services were worth. The most painful feature about the business was this: after all terms had been settled by letter (my sister wrote a beautiful letter and I left the correspondence to her), there came at the last moment a notice that I should be required to teach one young lady on the guitar. Now after years of study and all that painful practicing I could not tell when a piano was out of tune. What was I to do then with an instrument that required to be tuned every time it was used, an eternal winding up or down of its strings, all mysteries to me? My sister Elizabeth had an admirer who would often come to be-

[246]

guile the moonlit summer evenings in our garden with simple melodies on his guitar. He had been captain during the Mexican war, had commanded the Raymond Fencibles. The ladies of the county were so proud of their Mississippi heroes that on their victorious return to their homes they presented them with a magnificent banner of which the captain was the custodian. When he heard that I was to give lessons on the guitar he came forward with his own and presented it to me. He offered also to teach me as well as he could. I believe there was some pretense of my taking lessons from him, but the whole thing was such a farce that I was very miserable and lost all the joy I had felt in what had at first appeared a delightful adventure. The young lady who was expecting singing and guitar lessons from me haunted my imagination and I would have declared outright that I could not undertake it. But my father, who always believed that his children could do anything, persuaded me, as did all the others, that of course it would all be right. I imagined too that I had not been treated with entire justice in having those guitar lessons sprung on me at the last moment. In excuse for my father I must say he loved to hear me play on the piano, for we had very little music or musical talent in our village. When my sister and I arrived at the school I was much pleased with the appearance of things. There were so many big beech trees, also magnolias and a charming little stream in which I determined to wade where it wandered through the wood. The night before the first music lesson was to take place, I said to my sister: "Suppose I try to tune

[247]

that guitar now, I have plenty of time to do it in." She, trusting implicitly to my superior knowledge, assented. I then wound those strings up and I unwound them and I twanged on them till I saw there was no use in any further efforts on my part. But in the "dead waste and middle of the night" I was awakened by the sound of exploding strings. No signal guns booming their tidings of shipwreck over the sea could have sounded more dismal to my ear. All my strings broke at intervals. I saw I should have tuned them all down instead of up. All my hopes and confidence exploded with them and I determined that come what might under no circumstances would I ever again attempt to tune that intractable instrument. When next day the young lady appeared she was about my age, very gentle and very amiable. I said: "You will have to tune the guitar. You will find strings in the case." Then while I busied myself about the room she put the instrument in perfect tune, I presume, I took up her book of songs and asked which she liked best. She preferred "Mary of Argile." "Mary of Argile" suited me perfectly. I had never heard it before which was fortunate for me, for I was destined to hear it all that winter. After this had been sung and the young lady appropriately complimented I asked for another of her favorites, but I cannot remember the name of any other of them. They all became my favorites, but I have a poor memory for names. When the lesson was over this amiable and charming girl left me apparently perfectly satisfied. She certainly lifted a heavy weight from my overburdened conscience. During the course of the winter she even

[248]

took new songs into her repertoire, I paying the while such appreciative, flattering and undivided attention to the performance that she could not but feel grateful, I hoped. If she ever complained of her teacher I never heard of it. I believe indeed she was too amiable to do so. In the new year 1861 one of the Board of Trustees wrote us that as the school had fallen far short of the attendance expected, and as there were too many teachers for the number of pupils, some of them had to be dismissed. As we were the youngest it was thought proper for us to go. The gentleman concluded his letter by saying that his daughter had shed tears on hearing that she was to lose her music-teacher, whom she loved very much. She was my most advanced piano pupil and a very dear girl. My sister and I, instead of taking the four hundred dollars in gold offered us by the Board of Trustees, referred the matter to our father, who wrote that as the contract called for the whole school year it was bad faith to dismiss us sooner. He would therefore appeal to the courts. This was a legal decision, but hardly a wise, or even a just one. The war followed immediately and I have ever since had the satisfaction of knowing that I was not paid for what I could not have earned. My sister should have had her two hundred dollars and no more, I think, for the Trustees were perfectly right in what they wrote us. We returned then to our home in Raymond. The Secession movement which had begun before we left the boarding-school went on unchecked and soon the country was engulfed in a fratricidal war. Perhaps wars will never cease till the means for extermin-

[249]

ating the human race shall have attained such monstrous proportions that no people will be willing to submit to such inglorious and wholesale destruction, nor will wars long continue to satisfy the pugnacious instincts of mankind. My father and uncle were old line Whigs. They were against Secession and bitterly opposed to the leaders who advised it. They did all in their power to combat it, but young and fiery spirits were for it, and of course such politicians as hoped to benefit by the breaking up of old parties and of national ties. I was always, even as a small child, very fond of hearing my father and uncle discuss political questions, and would pull my chair close to theirs in our little parlor and listen with awe to what I considered to be words of purest wisdom. Then, all aglow with pride and enthusiasm, I would exclaim to myself: "Oh that the world could hear this! And learn what wonderful men my father and uncle are! Then they would be made president and vice-president, and our country would be the greatest and best-governed country on earth! And it would all be owing to the wisdom of my father and of my uncle!"

When I was still young enough to go barefoot in summer a young man was sent down from Virginia to Mississippi to cure him of the drink habit. It was an ill-advised move and his drunkenness killed him, but he exercised an influence over my life for many years. He saw me often with a book in my hand and easily persuaded me to promise him to read no fiction till I had finished with my school education. We had no public

[250]

libraries where books could be had. They were costly and difficult to obtain. I think the promise was detrimental to my mental development. I was continually going around asking people, "Is this a work of fiction?" Thus calling forth ever-renewed discussion on that subject, leaving me in doubt as to whether the Arabian Nights or Robinson Crusoe or the Pickwick Papers, when they appeared, were works of fiction or not. I dared not read any of them. There was a very good library at Burleigh, my uncle's plantation, but I stayed there very little. On a neighboring place was an only daughter and I was requested to spend my holidays with her. This young girl, exactly my own age, Agatha Moncure, afterwards married my eldest brother, Fred. The fact was I got very little to read and that little was in the nature of study, for I was slow and stupid and read very slowly indeed. It was at the Moncure home that I was thrown with the unfortunate young man who killed himself drinking.

When hostilities between North and South began Captain Elliot, the gentleman who had given me his guitar and who had tried to give me lessons on that instrument, brought me the magnificent United States flag of which he was the custodian, it having been presented by the ladies of the county to the Raymond Fencibles on their victorious return from the Mexican War. I was foolish and ignorant enough to cut it up for sashes for myself and friends which naturally I lived to regret. The blue center sprinkled with stars was made into a covering for a baby's crib. How beautiful it would have

[251]

been to send it to France in 1917, for no doubt its superb silk came originally from that country.

As the war progressed I began to have misgivings about the result and one day when my uncle was visiting us he, my father and I were alone in the parlor. I said to them that, as we were fighting for slavery, I did not believe that God would bless our cause with victory. This was like a bomb cast at the very feet of my uncle and father. It was considered treasonable to doubt our sacrosanct institution. I was severely scolded for what I had said, but I did not change my opinions, I only concealed them. When General Grant's troops passed through Raymond on their way to Vicksburg the Confederates, quartered in and about the town under General Gregg of Texas, were taken completely by surprise. The General had promised to take his midday meal with us that day. He was lucky if he got anything to eat on that occasion. When the firing began to be heard we were all intensely excited and rushed into the streets, especially into the one leading to the battle field. Soon some Confederates appeared bringing in a few prisoners. Some of the ladies upbraided these violently for invading our country. I, having obtained my ideas concerning the chivalry of war from Scott's novels, appealed to them in impassioned words not to disgrace our cause by mistreating unarmed and helpless prisoners. They were kindly women, only so terribly excited. From that day the ladies of Raymond had to nurse our wounded in the county court house for many weeks. When the news came of the fall of Vicksburg I went as usual to the hospi-

[252]

tal kitchen, but could not find the Irish cook. Hearing sounds from behind the door I found him hiding there and weeping over the fall of the city. I told him the Confederates would soon recover it. "It's not that, Miss," he sobbed out. "It's the boasting of 'em." I understood him to mean the Irish on the other side. In a friend's ward was a man wounded through the face. He was so profane my friend asked him to name his price. He said if he had red onions every day he would forego his profanity. The bargain was struck and red onions proved a moral influence of the highest value. One day loud screams of "Mary! Mary!" resounded through the halls. I was found and sent to a poor man who thought he was being devoured alive. I got my tin basin, warm water and soap and soon the wound was clean and neatly bandaged. That man was convinced that I had saved him from a loathsome death. When he was well enough to quit the hospital he sobbed over my hands as he pressed them in saying good-bye.

A neat ambulance drove up to our door one day and a stout negro man took out a young officer who had been wounded through both legs during the siege of Vicksburg. This was William Lynch Ware, my future husband. As soon as he was able to walk without crutches he returned to his regiment. Dreary weeks now followed. The country had been devastated in the path of the Union Army. I have often wondered how we lived at that time. My sister Elizabeth was housekeeper and she and my father always managed to find something to put on the table. I was very hungry in those war days

[253]

and I can never forget my sister's expression when I asked for more bacon, "Just a little piece." She hated to say no, but would whisper, "The servants must have their share."

We girls had a devoted friend of whom I cannot speak without deep and tender regret. Her name was Kate Nelson. She was about my age and when she came from her New Orleans school to join her family in Raymond, she was as beautiful a creature as I have ever seen. Nor was her beauty her sole charm. She had a voice in singing that went straight to one's heart, and her laughter was so fresh and spontaneous that it was irresistibly contagious. Kate came now into our family deliberations with an alluring proposition. She knew, I know not how, of a part of Arkansas where peace and plenty reigned, where the people were as warm-hearted and generous as their soil was fruitful and their climate genial. Let us go to this Paradise! We should be received hospitably and we could all find something to do there. Kate's enthusiasm was convincing. In the ardor of youth, impelled by the desire for relief from oppressive conditions and restrictions we adopted the idea enthusiastically. Our parents were won over. Three of my brothers were in the Confederate army. Business was stagnant. It was just the moment to welcome a change, as living conditions could hardly have been worse. I have never been to Arkansas, but an Arcadian vision rises in my memory whenever I hear the name of that state. The difficulty was transportation. Now Kate's home was a center for news; both soldiers and officers loved to go there. We

[254]

heard then that General Grant was giving away the wagons and mules driven into Vicksburg from the plantations on the route of his march. It was decided that Kate and I should go to Vicksburg and obtain transportation from General Grant in person with a safe conduct from him through the Union lines. One evening late, just as this decision had been reached, a lady of our acquaintance, Mrs. McCowan, came over to see me. She had heard that I wanted to go to Vicksburg. She could furnish a vehicle and a horse and would willingly take me if my youngest brother, John Davis, could drive us. She protested, however, that it would not be possible to take Kate, as there was positively no room for another person. She wished to start very early next morning and I must decide immediately. I felt that I could not afford to lose this opportunity, as time was worth everything to us if we were to secure the wagons and mules that were being given away. I was not happy, however, for I feared that Kate would be displeased with me. I could only urge my sisters to make it good with her. We got off very early next morning. My brother, though quite young, was an experienced driver, for it was he who made the weekly trips to Burleigh, my uncle's plantation, for meal, corn and an occasional piece of fine beef, or mutton when the family were there, but they were at that time refugees in Georgie, and that resource for us had been cut off. We reached Big Black station about the middle of the day. There was an important Union garrison at this point. We asked to see the Commanding General who assured me most courteously that our

[255]

horse, which needed rest very much, should be cared for and that meantime we were welcome to the hospitality of his tent. Soon after our arrival there, he invited us to dine with him. To have accepted dinner from a Union General would have been of course rank disloyalty, perhaps even treason, to the Confederate cause. We replied with thanks that we had brought our lunch with us. We partook therefore of this meager and unappetizing cold meal, while odors of the most alluring nature from that hot dinner came floating in to us. We were sustained, however, by the thought of our patriotic devotion to the Confederacy. While we were waiting there, women from the surrounding country began to collect in the tent. They came in all kinds of vehicles and told us they had come for the weekly rations which General Grant allowed them. I had not heard before that the Union army was feeding families in the devastated area. When the General came in from his dinner he said to the women that he had just received orders from Vicksburg to cease giving rations, as General Grant had been informed that they were used to feed Confederate soldiers. The women thereupon cried out as with one voice that they gave no food to Confederate soldiers, they had to feed their own children and the children of the negroes, besides the old people, they did not have enough to give away, etc., multiplying and emphasizing these asseverations. Hearing this and fully convinced that a great wrong was being done these poor women, I turned to the General and said: "Do you not believe them? I certainly do, and even if you do not, it would be more humane and more just to

[256]

give them time to make other arrangements instead of wasting it to come here for nothing." The General then told them that on his own responsibility he would furnish them rations for that week only, but that they must not return, as he could not possibly disobey orders I wish I could remember the name of this dear, good man. I was blinded then by prejudice nor could I read the hearts of men. As soon as the General left us, to give orders for the rations, and was well out of hearing, the women again with one united voice exclaimed, "Of course we feed Confederate soldiers! We would share our last crust of bread with them!" My astonishment was too great for words, nor should I have known what words to use under the circumstances. It was a case for casuistry. Were they wrong, believing as they did in the sacredness of the Confederate cause? Still they lied with too much ease. I could not get over it. We, in Raymond, had never refused a Confederate soldier food nor a place at our table. These women then had acted right, but why couldn't they have said, "Can we refuse food to the hungry? It would be unchristian," or better still, when to speak is to confess, why not keep silent? Well I felt that I had gone surety for a falsehood, and I was aggrieved against the women. But more exciting events were to follow. General Sherman came over from Vicksburg to meet his wife and daughter who were arriving from Ohio. The two Generals sat and conversed while waiting for the Sherman ladies. General Sherman's "stock" cravat worried him. He took it off and was awkwardly trying to arrange it. I, quite naturally, held out

[257]

my hand, took the cravat, stuck a pin into it and returned it to the General, but no sooner had I done this than the enormity of my conduct became apparent to me. It was indeed nothing short of high treason to the Confederate cause and I believed that if Mrs. McCowan betrayed me to the people of Raymond I should be ostracized, the finger of scorn leveled at me. I had henceforth, too, a dreadful secret which I feared to confess even to my most intimate friends, or to my family. Nor was the Sherman conversation of a nature to allay my scruples. He said he was persuading General Grant that the only way to end the war speedily was to burn and devastate the country, for the men would not remain in the Southern army if they knew their wives and children were homeless and hungry. He was so intent on demonstrating to his tenderhearted host the correctness of his theory that he took no thought of the two silent women on whom his words fell like the doom of an impending fate. Until the war was over this Sherman cravat episode was a torment to me. The two Generals now went out to meet Mrs. and Miss Sherman. They soon returned with the ladies. Mrs. Sherman was eager to tell the latest news, and very important news it was. The two men listened with rapt attention. The Confederate General Morgan who had attempted a raid into Ohio, from which the South had expected great results, had been captured and he and his raiders put into the penitentiary. On hearing this tragic news Mrs. McCowan and I began to weep silently, and for fear of attracting attention we slowly moved around till our backs were pretty well turned to the group of

[258]

talkers. We mopped the tears rolling down our cheeks, wrung our noses noiselessly, not daring to use our handkerchiefs otherwise, and were very unhappy. We were indeed a picture of the decaying fortunes of our poor Confederacy. Our hats and clothes looked as though they had come from a museum of ancient costumes. Mrs. Sherman and her daughter were dressed in the latest style, hats and traveling costumes in perfect taste and very "smart." The young lady was still very young, hardly fully grown. We would have gladly escaped to our vehicle but feared to call attention to our wretched selves. At length the Sherman party got off and we were free to depart. When we reached Vicksburg Mrs. McCowan and I parted, each going to our respective friends. My brother John Davis and I were received most hospitably by Mrs. Creasy and her mother Mrs. Pryor whom we had often seen at our house in Raymond. Mrs. Creasy promised to take me next day to General Grant's headquarters. She said she knew one of his staff very well, Colonel Strong. This officer received us cordially as an old friend of Mrs. Creasy. We were taken immediately to General Grant. The General manifested, from the first moment of our interview, a decided inclination to make a joke of the whole business of the Arkansas move. Replying to his jests I informed him that we were going to a corner of Arkansas where he and his armies could not possibly penetrate. He promptly retorted that he intended going right there. He was inexorable as to allowing any kind of fire-arms to my father and brother en route, but was not averse to the safe

[259]

conduct through his lines. After many jokes which I have forgotten for I was only intent on securing those wagons and mules, he asked me to follow him. At the end of a corridor he opened the door of a large room where a young man was at work at a desk. Before addressing him the General asked me in a low voice if I didn't think the young man was very handsome. I suppose he was really handsome, but what did that matter to me, to whom he was simply an enemy of the Confederacy? Not wishing to lose time I replied carelessly, "I don't think he is as handsome as Colonel Strong." Of course Colonel Strong's beauty, if he had any, had made no impression on me, but I said what I did because it seemed at the moment the best way of disposing of the question of Rawlins' beauty and of getting down to business, namely, to wagons and mules. I had made my remark in a very low voice but now the General horrified me by calling out: "Rawlins, this young lady says you are not as handsome as Strong." Poor Rawlins, thus exposed to criticism on his personal appearance before his superior officer, got very red in the face. My fears led me to believe that I had decidedly jeopardized my transportation prospects, and I was far more unhappy than Rawlins could possibly have been. But the General ordered him to make out a paper entitling me to receive two wagons and four mules. When this precious document was safe in my hands my peace of mind was restored. In spite of deep seated prejudice I had to acknowledge to myself that General Grant was a very humane man, and I felt sure he could never commit a

[260]

cruel act, that he would inevitably err if err it were, on the side of clemency. In comparing the two men, Grant and Sherman, I felt and still feel sure that General Grant accomplished more by his kind heart than Sherman by his theory of ruthlessness. The latter took no thought of the soul of man which is not like that of any other of God's creatures. Men bend to force, but hatred smoulders in their hearts. All this, however, is only stating in other words the old truth that Christianity is true statesmanship in dealing with a conquered foe, that evil cannot be overcome with evil. That evening Mrs. Creasy took me to General McPherson's headquarters to get from him the order for two more wagons and four more mules for the Nelson family. Mrs. Creasy agreed with me that this was better than to ask General Grant for all the transportation. It occurred to me, however, afterwards, that one of these two Generals might well have mentioned my mission to the other, and then what would they have thought of a young woman who sought by deception to acquire more than a just proportion of the plunder of Southern plantations! This thought tortured me and I felt sure I could have confided to General Grant the whole story, and Mrs. Creasy was there to corroborate it, but it is my fate always to commit mistakes and repent of them when too late. When General McPherson heard my name, he said: "I read a letter from you to your brother when I was in charge of the prisoners on Johnson's Island." I said: "You should not have read a letter not intended for you." "But it was a duty enjoined on me to read all letters addressed to the prisoners. I should

[261]

not have allowed that letter to go through according to rules, but I did so notwithstanding." I remembered the letter very well. It was a denunciation of the Union army and, I am now willing to believe, both unjust and exaggerated, but my brother Fred told me after his release that it was a joy to his fellow prisoners when he read it to them. So, in spite of its faults it served the purpose of cheering those unfortunate victims who were expiating the folly and iniquity of mistreating Northern prisoners in Southern camps, the only stigma, I hope and believe, on the conduct of the war by the South. General McPherson now took out some letters he had received from Southern ladies proving how lenient he had been in carrying out his instructions, how he had sympathized with them in their unmerited sufferings, privations, etc. He wanted me to read them. Now if there was one thing I dreaded more than another it was to be asked to read strange handwriting in public. I was and am still singularly deficient in aptitude for reading script. My eyes are very weak, but that accounts for it only in part. I take more time to-day to read my correspondence than any of my family or friends. I was, therefore, unwilling to make a spectacle of myself before General McPherson and Mrs. Creasy and got out of it as best I could by asking him questions. Did he favor turning our slaves against their masters? Of course he could not discuss such subjects with anyone, certainly not publicly. Why he cared in the least for my conversation is more than I can tell. I suppose that being in an enemy country he was deprived of ladies' society. I am very sure that if

[262]

he had had cultivated women to talk to he would never have listened to me who had been born and bred in a town smaller than any Northern village; but whenever Mrs. Creasy would propose to go he would beg her to stay just a little longer, till that good lady, who took not the slightest interest in our conversation, got out of all patience and dragged me off. Next morning after breakfast, entirely satisfied with my two orders for transportation to that Arkansian Arcadia, I found in the parlor a trashy novel which was absorbing my whole attention. Indeed I was weeping freely over it, for one of my unfortunate characteristics was the easy flow of tears. My eyes had been weak from my earliest infancy and tears had the effect of making them positively unsightly. The whole careless happiness of youth had in my case been marred by this infirmity of the eyes. At this moment Mrs. Creasy came hurriedly into the room, calling out that General McPherson was on the front porch and I must come out instantly. No help in sight for me. I had to go on that porch, into the clear morning light which revealed pitilessly my swollen eyes. I was dressed, too, very badly, in a dress spun and woven in a small farmhouse near Raymond. Of course General McPherson was an enemy, but there was my wounded vanity whispering, "What a disillusion for the man who thought you worthy of his conversation and attentions yesterday evening." The General said: "I have ridden all over Vicksburg this morning, but I can find no harness anywhere." I had never thought of harness, but now piqued and mortified, I said: "So your gift was not a real one. You

[263]

knew I should not be able to get the wagons and mules to Raymond." Without appearing to notice this ungrateful and impertinent remark, the General said gravely, "I think I can give you some good advice. In the Confederate hospital there are some wounded men most anxious to leave. Give my order to them and if there is harness still in Vicksburg they will find it." He mounted his horse and rode away. I believe he was killed soon afterwards in Tennessee, one of the noblest and most chivalrous men produced on either side in that war. My one desire at that moment was to leave Vicksburg and get home as soon as possible. Without asking Mrs. Creasy to accompany me I started off immediately to the Confederate Hospital. There I was brought before the superintendent, a Northern man. I told him my business in few words. He looked at me with what appeared to be withering contempt, and said: "At your age young ladies in the North stay at home with their parents and leave business to men." I really did not need any more mortifications that morning, and this blow overwhelmed me. I handed him the two orders and said I was told to come there. I did not attempt to justify myself. I bowed to the storm, feeling very miserable and forsaken, with the one imperious necessity of getting home where everybody loved me and where I always had the feeling that I was a favorite, not that this was true, but there are families that have the gift of creating this impression in each member. When I reached home I found my uncle there, who had persuaded my father to rent out his Raymond house and move to Burleigh, my uncle's plantation.

[264]

The family were refugees and the slaves too had been taken away, so someone was needed to protect the property. My father was greatly elated by my success in Vicksburg for the wagons and mules would enable him to cultivate the kitchen garden and a field at Burleigh with the slaves who had not left us. Besides he needed them to move down to the plantation, ten miles distant over bad roads. The Nelsons, too, were easily reconciled to employing their two wagons and mules in hauling freight to and from Vicksburg instead of seeking adventures in for away Arkansas, so all praised me, especially when the first wagon arrived with the news that the other three would soon follow. It brought two Confederate lieutenants with gifts of flour, coffee and mackerel. Great was the rejoicing among whites and blacks in our household at tasting once more these almost forgotten delicacies. All four wagons were put to immediate use by both families. My father found no difficulty in renting his house and we were soon most comfortably installed in the plantation home at Burleigh.

One beautiful afternoon at Burleigh in early autumn, as I was returning from a short walk, I was perfectly amazed to find our garden invaded by Northern troops. I hastened to the house and learned that a company of soldiers had come from Vicksburg to get the cotton my uncle had sold to the Confederate Government. I was immediately sent to the Commanding Officer, a Colonel, I believe, to ask for a couple of soldiers as a guard for the house. I was to ask also that he do us the favor of having our mules and two horses put in the cellar for safety.

[265]

He granted both these requests. Later he came to the house and made arrangements with my sister Elizabeth for a supper that night for himself and his fellow officers. She told him we had neither flour, bacon nor coffee (true). He said he would send these articles and promised to pay fifty cents besides for each man's supper. My sister told the Colonel that our family did not own the plantation, we were only taking care of the house, that the war had greatly impoverished us and she asked him to leave us three bales of the cotton and have it put in the cellar, to all of which he obligingly consented. At the time of the arrival of the soldiers there was a large iron laundry boiler in the yard before the kitchen, in which a hog was being boiled to make soap. The animal had died and was considered fit only to utilize in that way. The soldiers without asking any questions of the servants helped themselves to the entire boiler full and consumed it. We only heard of this later. I hope it did them no harm for it was thoroughly cooked. We had constant alarms throughout the afternoon and night. The soldiers wanted to kill the deer in the park but with the guard we were able to protect them. We sat up the whole night on the front porch with the two soldiers who guarded us in order to keep them awake for prowlers came continually, trying to get the horses and mules from the cellar. We were six young girls in the house, my three sisters, myself, our faithful friend Kate Nelson, and our future sister-in-law, Agatha Moncure. Besides these there were our parents, my youngest brother John Davis and my little sister, Letitia. Kate Nelson sang her sweetest songs

[206]

throughout the night and we told anecdotes. The soldiers were highly entertained. When the day broke and their comrades left they too were anxious to be off, but we were so afraid of stragglers stealing everything from us that we persuaded them to remain long after the sun had risen, endangering their lives most certainly, for Confederate scouts would, I fear, have made short shrift of them had they been discovered. I have always hoped that nothing harmful happened to those two good men. When at length the debacle of the Confederacy took place those three bales of cotton were of immense help to our family. While we were still living at Burleigh word came that Lieutenant Ware was mortally wounded in the eastern part of the state. My father and a cousin of Mr. Ware's, my dear friend Anna Martin, now Mrs. Marion Douglas of California, accompanied me on the journey, in the hope that we might possibly find him living on our arrival. He had received a ball full in the chest, which, happily being somewhat spent, fell downward after piercing and shattering the breast bone. Mr. Ware asked that we should be married before my father returned home. With the help of his very capable body-servant, Norfolk, I nursed him slowly back to health. When he was able to walk once more we went to Burleigh where were gathered the two families of the Raymond Dabneys and the Burleigh Dabneys. My husband's only brother was there also recovering from a wound in the hip which left him very lame but apparently in good health. It was a gay household. The young people had been acting plays and when I arrived I was called on immediately to fill

[267]

the role of Mr. Hardcastle in "She Stoops to Conquer," my sole fitness for it being that I could wear my husband's clothes. However, he would not permit me to appear on our improvised stage without his overcoat. To offset this incongruous costume I made with great care a jabot for the Hardcastle shirt, but in the confusion of the green-room it was lost. To my inquiries of the various actresses "Have you seen Mr. Hardcastle's shirt?" The reply was invariably "no." "Can't you help me find it?" "Too busy." I was in despair. Was I to forego the effect on the invited guests of the fine jabot I had made, or was Mr. Hardcastle in his own house to button up his overcoat as though he were exposed to the winter’s blast on some highway? I felt the whole responsibility of the role but could see no help, so I sat down and sobbed. This drew the attention of the green-room to the seriousness of the situation and Mr. Hardcastle's shirt and jabot were soon found. I am ashamed of this episode but because it remains so clear in my mind I have given it. Not very long after this we paid a visit to New Orleans. There I was introduced for the first time to the opera and the theatre. The ballet fascinated me more than any other part of the performance and in my enthusiasm I exclaimed, "Oh what wonderful, what beautiful children!" Whereupon my husband hastened to inform me how far these fairylike creatures were from being children. I listened with horror, for my bringing-up had been strictly on puritanical lines. Springing up and turning to my aunt I said: "Aunt Martha, this is no place for us, let us go!" And in spite of the expostulations of my

[268]

husband we left the Opera house far more quickly than we had entered it. Mr. Ware followed much against his will, "a sadder and a wiser man." The ballet, after this somewhat stormy introduction, became later, a prime favorite, indeed the greatest attraction of the theatre to me. Graceful, rhythmic movements of dancers to the accompaniment of music charm me inexpressibly. As to the ballet girls I love to think they are as innocent and pure as they are graceful. They can be, then why shouldn't they? Those were carefree days, but others were to follow of a very different nature. My husband's brother, Sedley L. Ware, who was called by us Toby, one of the most beautiful young men I have ever seen, was taken with consumption and in spite of all the care lavished on him, died within the year. No one understood in those days the treatment of lung trouble. Mr. Ware took me to the plantation which was situated in the Yazoo River swamp on Honey Island. This place was of great value before the war as it was above overflow. But now the slaves were free and it was burdened with a heavy mortgage. As no interest on this mortgage had been paid during the war the original amount was greatly increased. The husband of the lady to whom it was due was most anxious for a settlement and came to the Island while we were there. I suggested to Mr. Ware that the cotton on hand at the prevailing prices would pay the debt and leave us free. But he hated this debt, said it was an unjust one and he would rather try a law suit than pay it. I pleaded that a mortgage on the land would have to be paid sooner or later, that the creditor was so

[269]

anxious for a settlement he would undoubtedly give the highest market price for the cotton delivered at our landing on the river. My arguments could not overcome his repugnance to the origin of the debt and his determination to consult his lawyer. This decision was fatal to our happiness and to our prosperity. The lawyer advised yearly payments over a long term of years and charged four thousand dollars for the advice. The price of cotton fell rapidly even before we could get it to the market. The rebuilding of the family residence near Jackson, which had been burned during the war, swallowed up a large sum of money. So many houses had been burned that building materials and labor rose enormously in price. We lived in that house near Jackson for twelve years, leaving the plantation to the care of overseers till our affairs became so desperate, that after giving up one piece of property after another, we finally sold the home place with its six hundred acres of land, mostly wooded, for less than half of what the house and furniture had cost us. The sacrifice of this home which had belonged originally to his grand-father and where he was born and passed his childhood was a great trial to my husband. His health was most wretched and he died the year after we moved up to the plantation. One year later I lost my second daughter, a child of six and a half years, of rare beauty and intelligence. I had lost my first daughter at Jackson when only one year old. Work was now my only antidote to grief. I hoped to clear the plantation from debt and to achieve finally financial independence. I had breakfast at four in the morning as an example to the

[270]

field hands. The place was in the greatest need of an enclosure. It needed also a new gin house and new machinery. I was able to get all these things done and put everything in complete repair. Freedom had given the negroes a great passion for litigation and numbers of them were in the habit of going fifteen miles to the county town to settle their disputes in court. I settled them on the plantation, and knowing thoroughly the character of my people I managed to satisfy them all. I made a superb vegetable garden in a spot left by neglect to weeds and brambles. In the midst of these varied occupations I received a hurried summons to Jackson from my creditor, Mr. Ned Richardson, from whom I learned that the judgment he held against the plantation had become barred by the statute of limitations. He wanted to know what I intended to do about it. I said: "You have changed the original interest rate from eight to ten per cent. Put it back retrospectively to eight per cent, and I promise to pay the whole amount." He agreed to this and having visited the place and seen the fine order in which everything had been put, he offered to rent it for a few years to settle the debt. I was so eager to get to California to my sister Elizabeth, to whom I had sent my son Sedley in the care of his Aunt Martha, that I could feel nothing but gratitude to Mr. Richardson for my freedom.

What a paradise was California in 1878 when I arrived there. I have seen many lands since then, but never one I thought the equal of California. It was before the time of insect pests, which came later to torment the fruit

[271]

grower. In the autumn the big wagons came into the town early in the morning fresh from the fields, heaped up with boxes of grapes, the dew still on them, and such perfect grapes! They have not their superiors in all the world. They were sold at one cent a pound. As there was no rain for some six months in the year the apricots in the gardens ripened to perfection and dropped one by one on the soft green sward under the trees, like a rich embroidery to the eye. The fallen fruit did not decay for a long time, but slowly dried. No one seemed to object to the passerby helping himself. When I stopped to ring a bell and asked for permission to eat a few apricots from the ground the answer was always "Why, certainly, madam." Then the cherries, the melons, the figs, and the prunes! These latter were new to me and most fascinating. Even before ripening they have no acidity. It is one of the sweetest fruits grown. I do not understand why the fresh prunes lose this sweetness by transportation to the east, for on the trees they are marvelously sweet.

But my poor boy was still suffering from malaria contracted in Mississippi, so we accepted an invitation to spend some weeks on a lovely fruit ranch near St. Helena, owned by Mrs. Heath. There my son threw off every trace of malaria. It was a regular grape cure, the fruit being eaten fresh from the vines. I too should have been strong and well with all care lifted from my mind, free from the bondage of debt and for the first time with a feeling of security for the future, but by my own want of good judgment and of moderation, I had brought on

[272]

spells of palpitation of the heart causing great weakness of the voice and a nervous dread of these attacks I could not control. One night I caused Mrs. Heath to be roused in the middle of the night. I said when she entered my room, "My friend, I feel that I am dying. My teeth are chattering, my heart is beating most irregularly. I believe the coldness of death is creeping over me." Without a word that sagacious lady turned and left the room. When she came back she had a very large glass of whiskey and water, mostly whiskey, and she commanded me to swallow it. I had never drunk so much before, but I obeyed. I was quite well next morning and I procured a bottle of whiskey, which I put on my night table. I had no desire to drink it; just to look at it quieted my nerves and gave me courage, for I said to myself: "What have I to fear when the remedy stands there close at hand ?" It is with genuine regret that I bear this unwilling testimony to what whiskey did for me in those days, for I am a thoroughly convinced prohibitionist and bless the day when that beneficent measure was passed. We left the beautiful fruit ranch and returned to Santa Rosa on receiving the news that my dearest brother, Dr. John Davis Dabney was hopelessly ill with yellow fever. He had been riding out of his little town after midnight every night, not even letting his body-servant know of his movements, to a camp of refugees from Vicksburg, Mississippi. There he nursed the sick and helped bury the dead till one morning before day as he was returning home the fatal disease seized him. Happily, however, he survived this attack and was sent later by the govern-

[273]

ment as a yellow fever expert to Cuba during our war with Spain. There my dearest brother was of little service to the army, for he was taken very ill himself and suffered severely. Until that time, that enemy of the human race, the tiny but vile mosquito, had been plying undisturbed its "busy toil" of inoculating into the human family all the poisons it could collect. If that war served in any degree to unmask this insidious foe, it was worth all the disgrace of embalmed beef and the deaths from preventable causes among our soldiers. I had a feeling at that time that we should have been too proud to fight that war, but as in its consequences it did so much good I think it justified itself. I left California with my son in the late autumn of 1880, choosing the time just before he was twelve years of age. He was much overgrown, and like all boys under similar circumstances, seemed to take up much more than his share of room on the train. No conductor had uttered a protest against his half-price ticket till the night before we reached Vicksburg and then one, more vigilant than the others, eyed the boy narrowly and asked: "What age is that boy?" "He will be twelve tomorrow, the fifteenth of November." He gave an incredulous grunt and observed, "He'll not travel on a half-price again." "You are perfectly right, sir."

When the time came to take back my plantation, which had been rented out, I went up to my brother's home at Tchula on the Yazoo River, or rather on the Horseshoe Lake formed from it. When the negroes heard I was there, my particular and faithful friends, among them came to see me. "Miss Mary," they said, "that overseer

[274]

of Mr. Ned Richardson done opened that ditch near the corn cribs and the stable, and all night long when the water is high you can hear the ground tumbling in that ditch. It's so big and wide now, it's going to carry off your cribs and your stable into the river." After hearing this report from my good colored friends I could not sleep at night. I could hear the whole time the earth caving into that ditch and being carried off by the raging flood. My brother begged me to go abroad and put the ocean between me and Lynchfield. He promised to take charge of everything for me, a promise he more than fulfilled. My lawyer advised me to bring suit against Mr. Richardson, promising at least ten thousand dollars in damages. This idea I did not entertain for a moment. It was Mr. Richardson's confidence in me which caused his securities to expire by the statute of limitations. But even if it were true, as others said, that his confidence was in the improvements I was putting on the plantation, still he had lifted that burden of debt from me, given me freedom from care, thereby most likely saving my life. All that I could not forget.

I commenced in California the study of languages which suited me better than any other occupation. I found in Santa Rosa a French family and a German one where I arranged to spend four hours daily, two in the morning and two in the afternoon, talking and reading those two languages. I can never forget that wife and mother in the French family. There were no other French people in Santa Rosa, whereas the Germans formed a prosperous and happy community. I began

[275]

my lessons with Madam G. by asking her to recount the story of her life. It was a very sad one, and the first day she shed many tears over it. I gave her my unqualified sympathy, but I understood very little of what she said. Next day I begged her to repeat the story, which she did with fewer tears, and as day after day I asked as a special favor the same history, she learned to tell it with cheerful equanimity and great improvement of style. I learned a lot of French and this good woman became far more resigned. She had received much genuine sympathy from me, and things seemed to look brighter to her, just as the poets, singing their woes to a listening world, find consolation in the universal sympathy they inspire. They cast their griefs out of their own hearts while planting them in the hearts of others. The best German teacher I ever had was in Richmond, Virginia. She was far more cultivated than any of my previous ones. She and I read Goethe together. In spite of the great beauties of Faust I could not enjoy a tragedy. They always affect me painfully, especially when read for the first time, so one day I stopped reading and exclaimed, "I don't like this man Faust! He has taken Mephistopheles as his confederate and between them what chance, I should like to know, has this poor girl Marguerite ?" I was in such dead earnest that I did not perceive the effect of my words on the classical mind of my friend and teacher. Next day she said: "I thought of your criticism of Faust in the middle of the night and got in such a laugh that I waked my husband, who asked in amazement, 'What on earth are you laughing about at this hour of the night!'"

[276]

But I really can take no pleasure in a tragedy unless the guilty alone are punished. King Lear is far too painful, whereas Macbeth is much less so to me.