Major General Earl Van Dorn, known as Buck or Van in the army, son of Judge Peter Van Dorn and Sophia Donelson Caffery. Born 17 Sep 1820 at Port Gibson, MS, m. Martha Caroline (Carrie) Godbold (1827-1876), d. 19 Jan 1863 at Spring Hill, TN.

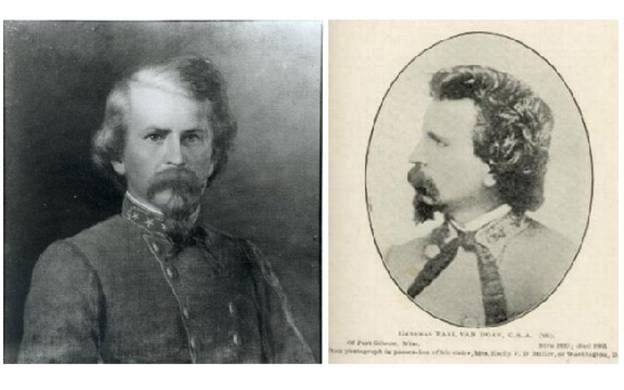

In 1861, in Virginia, a correspondent described Earl Van Dorn, “The General is rather under-sized—of a spare frame, erect and graceful in his movements; his mustache is long but light; otherwise he is closely shaven, which is one cause of his youthful appearance. His uniform was a gray tunic, with buff collar and cuffs, heavy gold braiding on the sleeves and three stars on each side of his collar, the one in the center being the largest; as he drew back on his buck gauntlets, I caught sight of a cross, embroidered thereon in scarlet silk an ancient symbol of rank.” Maj. Gen. Dabney Maury described him, “He used to ride a beautiful bay Andalusian horse, and as he came galloping along the lines, with his yellow hair waving in the wind and his bright face lighted with kindliness and courage, we all loved to see him. His figure was lithe and graceful, his stature did not exceed five feet eight inches, but his clear blue eyes, his firm set mouth, with white strong teeth, his well-cut nose with expanding nostrils, gave assurance of a man whom men could trust and follow.” With his classical education, he was erudite and cultured; his writing was laced with French and Latin. When the subject of a Confederate national anthem came first arose, Van Dorn leapt to the tabletop and sang lyrics adapted to Bellini’s I Puritani. He was an accomplished painter. From a letter to his wife from TX in Apr 1856: “I have a new set of paints given to me by Mrs. Colonel Albert Sydney Johnston, and my favorite pastime—painting—will fill up and consume some of these long hours of summer.” Van Dorn was well-regarded by his troops. Pvt. A. W. Sparks recalls, “His name is not now remembered but his fame, we private soldiers consider, should stand alongside with Napoleon, Lee, Grant and others of like fame, but greatness in like matters is too soon to be forgotten, but all old soldiers of the corps, will bear testimony that, like old Van Dorn, he fought all that came in his way regardless of numbers, and his old A. Q. M. [quartermaster] supplied all things that he could get regardless of expenses.”

Earl Van Dorn was sent away to Baltimore for his education. He longed for a military career, and wrote to his uncle (by marriage), former President Andrew Jackson, asking for an appointment to West Point. Jackson obliged, and Van Dorn became a member of the West Point class of 1842, in which he graduated 52nd out of 56 men he was to later fight with and against in the Civil War.

Following graduation, he was posted to Alabama where he married Caroline Godbold when he was 23 and she was 16. He was to seldom see her for long periods, as he was forever off fighting battles. He fought in the Mexican War under Zachary Taylor, Persifor Smith, John Quitman, and Winfield Scott, with fellow officers Jefferson Davis (who married Zachary Taylor’s daughter against Taylor’s wishes) George B. McClellan, George G. Meade, Robert E. Lee, Ulysses S. Grant, P. G. T. Beauregard, and Braxton Bragg, against Santa Anna’s Mexican Army. (It has been said that the Mexican War was a training ground for Civil War generals.) He fought in the taking of Vera Cruz, Chapultepec, and Mexico City. At Fort Brown he dashed a hundred yards outside the fort through round shot, canister, and shells from the enemy batteries to re-hoist the U.S. flag which had been shot down. He was wounded in the foot at Mexico City. After the occupation of Mexico City ended, he served in Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi, then appointed Captain with the new 2nd Cavalry, formed by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis to fight Comanche Indians in Texas. The 2nd Cavalry was commanded by Albert Sidney Johnston, with Robert E. Lee as second in command, and had a regimental march composed by Van Dorn’s sister Emily. In the “Wichita Expedition,” Van Dorn was severely wounded by two arrows, one through his wrist, and one passing through his rib cage. He managed to push both arrows out through their exit points, to prevent the arrowhead from detaching inside his body, and miraculously escaped death. The Wichita Expedition proved an embarrassment to the Army. Because of poor communication, the operation was launched at the same time a treaty was being negotiated at a different fort with the Comanches. Attacks against the Comanches continued, however, responding to pressure from settlers who were subjected to loss of life and property from Indians. On the left, below, is seen Earl Van Dorn in a Federal uniform in 1860 with a sword that was presented to him by the Mississippi Legislature.

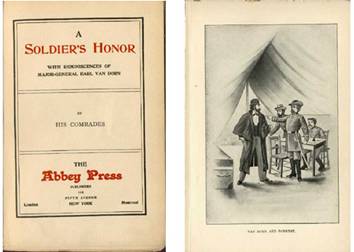

In 1860, Van Dorn and other officers were caught up in the tension between the North and South. Van Dorn was described by a fellow officer as “an ardent advocate of the right of secession.” He was in temporary command of the 2nd Cavalry when he decided to resign, but awaited the return of its then commander, Robert E. Lee, to submit his resignation, effective 31 Jan 1861. Appointed a Confederate general, he was sent to familiar ground in Texas, and with a few men captured the Federal steamer Star of the West which had come to evacuate Federal troops from Texas as the war started. The Federal troops surrendered their weapons, and those who did not join the Confederates were paroled. This success was much heralded because the Star of the West, of Fort Sumter fame, was the first naval prize of the Confederacy. In Sep 1861 Van Dorn was posted to Virginia. In Jan 1862, after the Battle of Manassas, VA, he was sent west. His army suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern (or Pea Ridge), AR, in Mar 1862. Van Dorn’s troops included a regiment of Choctaw Indians, slave-owners themselves and Southern sympathizers. After the battle, Van Dorn received a message from the Federals, “The General [Curtis] regrets that we find on the battlefield, contrary to civilized warfare, many of the Federal dead who were tomahawked, scalped, and their bodies shamefully mangled, and expresses hope that this important struggle may not degenerate to a savage warfare.” Van Dorn replied, agreeing that such behavior was unacceptable, but entered a counter-complaint that many of his men taken prisoner had been murdered by Federals who were said to be Germans. Following Elkhorn, from May-Sep 1862 he commanded an admirable defense of Vicksburg, which was under continual assault by Federal gunboats on the Mississippi River. He then led an assault on Corinth, MS, which failed. An interesting story is told in Gen. William T. Sherman’s memoirs: sometime after the Corinth retreat, Sherman heard that his old friend from West Point days, Van Dorn, was very short on supplies. Sherman dispatched cigars, liquor, boots, and gloves through the lines for the Confederate general’s personal use. Van Dorn was next placed in charge of cavalry, and on 20 Dec 1862 had a major success with a lightning raid on Grant’s supply base at Holly Springs, MS, capturing or destroying over $3M in supplies. Van Dorn’s division had ridden over 500 miles in two weeks, most of the time through enemy-held territory. It is said that this raid delayed the fall of Vicksburg by 6 months. In early 1863, he joined with Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry in Tennessee for successful raids. Forrest and Van Dorn had a dispute which very nearly led to a duel, over the disposition of supplies captured by Forrest. The illustration below is about that incident, which ended with Forrest saying that he had enough Yankees to fight without fighting Van Dorn.

Then, suddenly, Van Dorn was dead—not by enemy fire, as he would have liked—but at the hands of a jealous husband. While in Spring Hill, TN, near Nashville, Van Dorn had spent much time with the young Mrs. Jessie Peters, visiting her plantation and taking carriage rides with her. On 19 Jan 1863, her husband, Dr. George Peters, came to Van Dorn’s headquarters to ask the General to sign a pass for travel through the Confederate lines. While Van Dorn was signing the pass, Dr. Peters shot him in the head and escaped, pass in hand, before Van Dorn’s aides (including his nephew Col. Clement Sulivane) reached Van Dorn’s office and raised the alarm. Dr. Peters was eventually captured in Mississippi and tried and acquitted by a Confederate court, his defense being that he had been defending the sanctity of his home. Jessie Peters maintained until her dying day that nothing improper had occurred between her and Van Dorn. But rumors abounded, even that he had been seen leaving the plantation in the middle of the night and that he had actually been shot at the plantation and was taken to his headquarters as a more acceptable setting for his death. His family believed that Dr. Peters was a Union spy and that the shooting was an assassination.

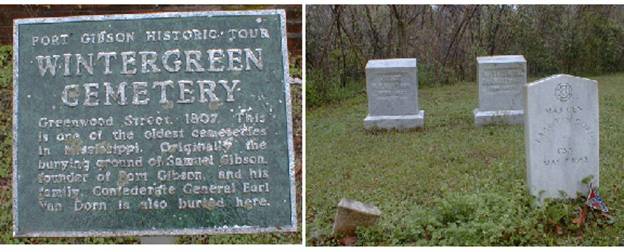

Earl Van Dorn could not be buried in his hometown because it was in Federal hands. He was buried in the Godbold family plot on his in-laws estate at Mount Vernon, AL. An eyewitness reported “As we watch the immense procession of soldiers the hearse drawn by six white horses, its gorgeous array of white and black plumes, that bore the grand casket in which the dead hero lay, we thought with sorrow of the handsome face still in death and the heartbroken wife, thus cruelly widowed. His little daughter was the chief sorrower visible at his bier, the wife being too prostrated with grief to leave her room.” In November of 1899, Emily Miller, with the help of her son T. Marshall Miller, had her brother’s body disinterred. She accompanied the casket by rail to Port Gibson for reburial next to his father in Wintergreen Cemetery, both stones facing south toward the Van Dorn home, as the Judge wished. At Port Gibson, the casket was opened, after more than 30 years of interment, and the remains were found to be in an excellent state of preservation. “The form was clad in the Confederate gray uniform of a major-general, the belt, buckles and epaulettes being intact, and around his shoulders were the soft golden curls familiar to soldiers on a hundred battlefields as the intrepid warrior rode at the front of his men and urged them to battle.”

The consensus on Earl Van Dorn is that he was a soldier of outstanding bravery, but that his esteem for glory and honor kept him from carrying out effective campaigns with large armies. The impetuous Van Dorn attacked straight up the front of a defensive enemy, in the face of artillery and breastworks, with no reconnaissance. Van Dorn was planning a second attack on Corinth, following his defeat there, but reconsidered and abandoned the plan after a friend said, “Van Dorn, you are the only man I ever saw who loves danger for its own sake. When any daring enterprise is before you, you cannot adequately estimate the obstacles in your way.” After failures at Elkhorn Tavern and Corinth, where he was clearly out-generaled by Curtis and then Rosecrans (his classmate at West Point), he was never again to head an army, but was placed in charge of smaller cavalry units, and he excelled.

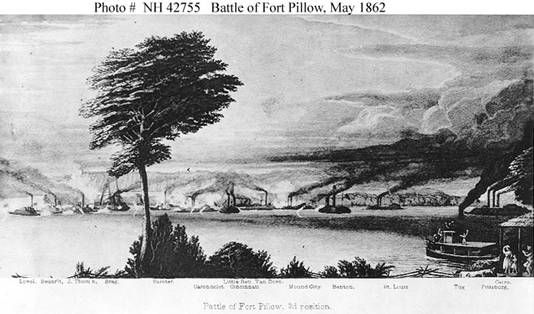

Naval Historical Center engraving, Battle of Fort Pillow, TN, 10 May 1862, involving the CSS General Earl Van Dorn (center of picture).

From a letter to his sister Octavia from Mexico in 1846: “Don’t you poor helpless female population wish you were men so that you might snatch a sword and join in the game for glory? What does the gambler know of excitement who has millions staked on a card? He loses millions, he can win but millions. But here life is to lose—glory to win. Who can know what the bosom feels, how the heart swells with burning emotions, hopes, proud longings for distinction.”

This feeling was probably common; his nephew Clement Sulivane wrote to Van Dorn’s sister Emily in 1862: “I have had the honor to be under fire, and have stepped over the bodies of the slain.”

Of the flag-raising incident at Fort Brown, Van Dorn wrote home, “I dodged several bomb-shells which threatened to fall on my head. I skipped out of the way of a rolling howitzer ball…musket balls flew around me at one time like a thousand humming-birds—so I had the sound of all kinds of music.”

Southerners thought the Civil War would be over within months; Earl Van Dorn wrote to his wife, on 29 Nov 1861, before the Battle of Manassas: “It may be, I think it probable, this war will not last longer than this winter.” But it became clear that was not to be. Van Dorn wrote his wife on 6 Apr 1862, after the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern: “I expect to grow gray before the war is over.” Furthermore, he assumed, as did other Confederate leaders, that if the South lost the war, he would have to flee. In the same letter to his wife, Van Dorn said, “This is a terrible war, but we must see it through, and have our country come out of the struggle with honor and independence. If we do not I must look for a home in some other climate—South America or Mexico.” Indeed, his cousin, Confederate Maj. Gen. John George Walker, fled to Mexico after the war, then to Cuba, and finally to England, returning to the U.S. in 1868. (Jefferson Davis spent two years in prison.)

Carrie Van Dorn was described by Emily Miller as a “girlish-looking little woman …modest and shy, slight and graceful…” She was the daughter of Col. James D. Godbold and his wife Olivia. Her name appears often as “Carey” or “Cary.” Earl and Carrie Van Dorn had two children, born at Mount Vernon, AL, where Carrie lived with her parents: (1) Olivia, 1 Apr 1852 – 4 Feb 1878, m. Frank Aubrey Lumsden 8 Oct 1868, 4 children; and (2) Earl, Jr., 27 Jul 1854 – 3 Apr 1884, never married. Carrie died 19 Jan 1876. Earl, Jr., wrote to his Aunt Emily, “It is sad to announce the death of my dear and beloved mother. She departed this life the 19th of January. I received your kind letter and answer immediately. I appreciate your effort to get employment for me, and would like to accept, but I feel so incapable of any kind of responsible business on account of my inferior education that I should be at a loss what to do. I will leave Alabama soon. I do not feel that there is anything more on earth dear to me since I lost my dear mother, —you are next to her, and I look on you as a second mother to me. I must love one my mother loved as she did you. Please have my mother’s death announced, and will you write her obituary? Earl Van Dorn, Jr.” Earl, Jr., became a civil engineer in Monroe, LA, and died 3 Apr 1884, and is buried in the Monroe City Cemetery.

Earl Van Dorn and Martha Goodbread (abt 1836 - early 1870s) had three children during the years he was stationed in Texas. Family members feel that it is unlikely that his Mississippi family ever knew of the Texas family. A son Percy Van Dorn was born in Texas in 1857; a daughter Lammie Van Dorn in 1858; and a son Douglas Van Dorn in 1860.

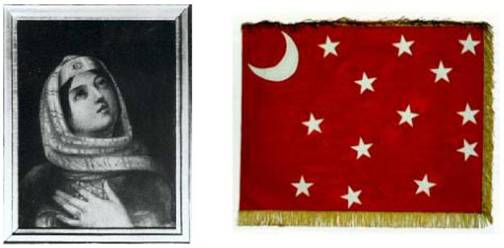

Below is a painting by Earl Van Dorn. The painting is said to be of his niece, Sarah Van Dorn Lacey, the daughter of his eldest sister Mary. The painting is undated. On the right is the Van Dorn battle flag, one of several variants used by Van Dorn troops during the Civil War.

Van Dorn’s exploits were mentioned in several of Faulkner’s books, The Unvanquished, Absalom, Absalom!, Light in August, and Sartoris/Flags in the Dust. Three books have been written about Earl Van Dorn: A Soldier’s Honor, by His Comrades (Abbey Press, New York, 1902), assembled by his youngest sister Emily Van Dorn Miller; Van Dorn, by R. G. Hartje (Vanderbilt University Press, Nashville, 1967); and The Tarnished Cavalier, by A. B. Carter (University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, 1999), the latter being the most interesting and well-researched book on Van Dorn. Also, The War Between the States as I See It, by A. W. Sparks, online at http://www.civilwarancestor.com/. See also They Sleep beneath the Mockingbird, by H. A. Cross (Southern Heritage Press, Murfreesboro, TN, 1994) on his burial. The photographs are from these books or the Internet (most originate with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, and most of those are from Emily Miller). The painting by Van Dorn is from the MDAH.